WORTH THE READ by Gordon Walmsley

Lene Henningsen, Denmark’s poet of careful intuitive probings, has produced seven or eight books of poems since she arrived on the scene in 1991. Her work evokes a variety of response. Some regard her as a supremely gifted poet, while others have no idea what she is talking about.

In this sense she shares something with Ireland’s Medbh McGuckian who also has her enthusiasts and yet who is not for the reader devoid of intuitive capabilities. Not everyone is able to shake Lene Henningsen’s poetic strong box so as to elicit a revealing coin that might clang to the floor. With some poets, you need to return again and again to their poems, sleep on them, return again.

Her work is more suggestive than explicit. She notices certain configurations, certain patterns, sketches them in poetic form without crystallizing her observations into a personal dogma. She lets her observations stand. Thus observation is never allowed to transmogrify itself into observance. You feel her project is the grand project of “the search”. And while she exhibits a reverence for the enterprise of I-Would-Know she is skeptical of formulations that might reduce her experiences to a two-dimensional plane.

This reluctance to express markéd opinions, to pigeon-hole, is a characteristic Nordic aversion, an aversion that may be traced at least as far as the Reformation and which embodies a healthy distaste for the untested thought, for dogma. Things are not black and white, a Dane might say. And why should one impose one’s opinion on the reader? Shouldn’t the reader be free to form his or her own judgments? This is a very Scandinavian way of thinking. (This point of view, of leaving the reader free, even goes so far that publishers almost never provide the reader with any form of biographical information about the author of a book of poetry. You get the book and that’s it.)

And yet, Lene Henningsen wants to know! Know what? Know about this world. So how do you begin to comprehend it and, being a writer, how do you make a book that is helpful to the reader who also may want to know what is going on about him. Without badgering him with your opinions? And what about the big questions? Shouldn’t we consider those too?

Thus emerges, Ms. Henningsen’s most recent book which she calls Mærket Umærket. The book imagines itself as an Essay, which seems to me an extravagant misnomer. For there is something of poetry in it (meaning, loosely, a progression of artistically formed phrases) drama (meaning that several characters make their appearance), and symposion, (meaning that a group of individuals sit together to consider some object of investigation.)

The title in English might be rendered in its double meaning as Noticed (or touched) Not Noticeable (or that which can not be touched). Thus it is a typical Lene Henningsen formulation. It says and yet does not say. For how can something that is touched or noticed be incapable of being touched or noticed?

Mærket Umærkeligt posits four “characters: the word, the star, the myth and, yes, the wine. We might say, in English, Word, Star, Myth, Wine. The characters and their questions derive from real-life conversations, the author insists on telling us. These ur-conversations with a psychologist and a wine producer are duly credited in the introduction to the book. Ms. Henningsen has extrapolated, interpolated and embroidered these talks so that the book reflects her own investigative expanse.

“I would like to invite you all to a conversation about everything,” says The Word who thus initiates the ensuing series of dialogues. “I will start things off with the beginning. We are back in the beginning’s darkness and cold where there seems to be nothing at all….”. To which The Star replies:

“I really must break in here at this point with a remark. In the beginning there was warmth, content, matter. Everything concentrated in a single point where there seemed to be nothing at all.”

Myth then says, “we can just as well start with darkness. We are in a myth, a personal universe, where all investigation must take its point of departure.”

And then says Wine: “Winter’s darkness, yes. Here lies the beginning of a new chapter, a new year.”

And thus we embark on Lene Henningsen’s journey into trying to understand the things of this world, in concert with other distinct individuals, with distinct perspectives and interests.

Mærket Umærket is a book that is not easily categorized. But it is a book that stimulates. The whole epistemological question of how we know things is the being that informs it. And in this day of “statements”, from politicians, cultural personages and small children, the gentle task of knowing is not wholly irrelevant.

Mærket Umærket.

by Lene Henningsen.

Borgens Forlag 2008

Denmark

SKYBRUDD I REGNSKAPET by Jon Eirik Lundberg

The great deception of so-called “post-modernism” is this: everything is a lie so you might as well lie in a way that has insight and genius.

The problem is that in accepting the postulate of the lie, a writer never bottoms out; he never becomes fully part of this earth. He is in a constant condition of…hovering. And thus he never learns…reverence.

That is the danger of the merely humorous. The world is put at a distance and is never to enter in. Perhaps humor is truest when it is part of a greater earnestness. Though mere earnestness is a kind of illness. Earnestness needs a dose of humor if it is to be in balance, sane, in touch.

The perfect representative of the non-ideological (or even the disingenuous) is the fragmented, multiple personality. Passau is the fiction that speaks to a generation of fractious post-moderns. Passau of the several distinct personalities.

Some of the poems in Jon Eirik Lundberg’s book of poems Skybrudd I Regnskapet (Downpour in the Tallying up or, playing on words, Downpour in the Rainscape) feel like hookah pipe poems, meaning that they are like plants whose roots have been clipped.

MIN FAMILIE OG ADOLF HITLER

Jeg hadde elleve onkler under krigen

De ble alle sammen arrestert

I en kino i Hardanger

Da de nektet å reise seg

For de tyske soldatene

Som ville forbi knærne deres

Interneringen gjorde dem så harde og forknytte

At de ble kastet ut fra fly

Som bomber

To brødre i Atlanterhavet mot et britisk hospitalskip

Tre over Jan Mayen mot russiske ubåter

Fire onkler blåste støvet ut av Londons nattklubber

(Og falt neste kveld som duskregn

På noen fiskekuttere nær Irskekysten)

Én onkel bommet på Den Transsibirske Jernbane og ble dikter

I New York

Den siste kastet seg selv ut over sydpolen

Og slo hjertet sitt opp som et flagg der

Farmor ble hentet av Gestapo

De satte små vinger på henne

Og skjøt henne over Den Engelske Kanal

Rett inn i London Docks hvor hun gjorde ubotelig skade

Det var så vidt hun kunne snuble ut av ruinene

Og samle sine sønner fra alle krigens hjørner

Og be dem glemme alt de hadde sett tog hørt og gjort

Og trøste seg med at vår egen grandonkel

I New Mexico-ørkenen

Ville hoppe ut over Japan frivillig:

Én gang for sin mor

Én gang for oss

Og falle som kunstig sne på selveste solen etterpå…

…

Within the confines of mere humor a writer can only knock his head against the wall, again and again and again if his intention is to break through into something resembling the truth. For humor is not a sense organ in itself and risks being self-encapsulating in a false opposition to the heart, if it is not used in combination with a greater earnestness.

The tone of Skybrudd I Regnskapet is absurd humor. Humor embodying paradox, word play and the noting of clichés and common expressions turned on their nose. If this is all the book were it could be tossed off as superficial chatter.

But when the first layer is burned away by the observant reader, something else reveals itself. And the reader begins to sense a deeper earnestness.

The point of departure seems to be humor. The question then becomes whether the book will end as a closed circle or an open spiral?

ARVEN

Faren min avlet biller og oppfant hjertesykdommer

Kundene kom i hopetall fra hele landet

Med øynene oppsvulmet av gråtetørst

De spiste alle billene

De slukte piller så hjertet brast

Jeg glemmer aldri

De sprukne smilene

Og de salige, sønderknuste blikkene

Når smerten satte inn

Og drev dem ut i vanviddet

Siden tok de hele gården

og far, og glasskolbene

og alle reseptene de spiste ble til genetiske koder

de ble skaltet av sine egne barn

som igjen ble spist av sine, og så videre

Jeg for min del holdt pusten i tolv lange år

På bunnen av en mørk og skitten flod

Sølvkroker danset rundt meg dag og natt

Inntil de fant en annen, druknet stakkar

som de spikret opp til tørk på et trestativ

The element of surprise isn’t enough. In the same way that mere humor isn’t enough. Unless one senses something deeper the whole enterprise can go astray and be just well, surface imaginings. These poems are essentially lyrical and you feel an intensity behind the rhythmic loops, an inner conviction that seeks to break through the con man’s Oz-like veneer of the world into a greater perception of things. Lundberg’s own intensity seems to want to burn through this falseness by exposing it, laughing at it, pointing to it.

FORRÆDERI

Under en bro, der skal du bo

Du som går ned langs røttene

Til husene smelter som fjell

I lyset fra eksploderende kaffekanner

Tilbake til årene som etterlot sirkler

I kanalenes blekk

Der skal du servere dem Sannheten

Og der skal de skyte deg

Med fremtiden som en drink i høyre hand

En tørst hvesende innpåsliten drink

En drink så sterk at bardisken svever

En drink så berømt at sukkeret synker

En drink så tidlig at solskinnet knekker

Under en bro, der skal du bo

Med fortiden som en lunge

Du som redder alfabetet fra søppeldunkene

Og børster fluene av deg selv som den du er

Jon Eirik Lundberg has written a book whose point of departure seems to be humor. But the real point of departure is a wound. The wound caused by some source of hypocrisy he would flail the life out of, exposing it in its full absurdity. And then what?

We shall see.

SKYBRUDD I REGNSKAPET

Jeg ser på tallene

Og tallene gir meg ris med gondoler

Tallene graver et hull I permen

Så bokstavene kan kravle fritt

Tallene bærer pyramider inn og ut

av setninger

Og smiler til paddenes forlatte ansikt

I sanden. De avsagde brevene

Drysser stille ned

på fortiden

Og tar fyr.

Jeg ser bare på tallenes tall

Og tallenes talls tall, etter fire

Kommer ni. Og tallene

Byr på stupebrett

og tørt vann

Jeg ser på tallene

Og tallene glaner tilbake

Tallene maler honningen

gul som selvbedrag

Tallene drikker en fjellkjede

Og skjærer barndommen løs

Fra kornaksets ranke holdning

Husene blir til gravsteiner

Og veiene kler seg ut

som gress. Når timene smelter

Vokser der mugg på hver setning.

Jeg ser bare tallene

Og tallene gir meg ris med gondoler.

Skybrudd I Regnskapet. By Jon Eirik Lundberg.

Aschehoug.2008.

In Norwegian

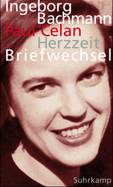

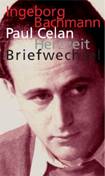

From Germany, the venerable Suhrkamp Verlag has put out a book called HERZZEIT, which reproduces the correspondence of the Austrian writer Ingeborg Bachmann and the Rumanian writer Paul Celan (born Paul Antschel). That correspondence has been buried in archives until now. The book also contains correspondence between Bachmann and Celan’s wife, Gisèle Celan Lestrange, as well as correspondence between Celan and the Swiss writer Max Frisch.

From Germany, the venerable Suhrkamp Verlag has put out a book called HERZZEIT, which reproduces the correspondence of the Austrian writer Ingeborg Bachmann and the Rumanian writer Paul Celan (born Paul Antschel). That correspondence has been buried in archives until now. The book also contains correspondence between Bachmann and Celan’s wife, Gisèle Celan Lestrange, as well as correspondence between Celan and the Swiss writer Max Frisch.

How strange it must have been to be in Vienna in 1948. Vienna! At the turn of the 19th century and the period preceding the first world war, Vienna was a place of many and varied muses. Sigmund Freud, Gustav Klimt, Arnold Schönberg, Arthur Schnitzler, Gustav Mahler,Wittgenstein, Hofmannsthal are some of the names associated with Vienna then. After the second world war it must have seemed like a desert filled with memories. Vienna had been bombed 52 times during the war. In 1945 the British and the Americans had dropped 80,000 tons of bombs, destroying over 12,000 buildings and killing about 30,000 persons. Even the zoo had been bombed. 300 bombs had been dropped there, killing over 2000 animals.

This is the Vienna where Paul Celan and Ingeborg Bachmann met in 1947/1948. Celan came to Vienna from the East (he grew up in Czernowitz. which now belongs to the Ukraine but which then was part of Romania). He had survived a concentration camp, though his parents had not. He was a German-speaking Jew, a supremely gifted fledgling poet and he was fleeing. Fleeing to…somewhere… a saner place perhaps, carrying with him memories that would eventually bore their way into his soul, destroying him. Ingeborg Bachmann was six years younger. She was writing a dissertation apparently critical of Heidegger (I confess to not having read it) which, according to Karen Achberger’s concludes that “Heidegger's philosophy cannot legitimately make any claims to truth and that it is art alone, and not philosophical discourse, which can speak truly about the world..."

Bachmann’s father was an early member of the National Socialist Party. Thus it was, the daughter of a Nazi and a Jew, whose family had been eradicated by the holocaust, fell madly in love with one another other. One tries to imagine them living together, but life seemed to have had other ideas. Celan moved to Paris. Ingeborg Bachmann stayed in Vienna. Later she would move to Rome.

Their correspondence reflects their attempts to fight what one senses is their struggle to continue their relationship, despite the urgency of destiny, karma, or the individual courses of their rivers. Two sensitive people living in the aftermath of a horrible war, who were crazy about each other but who could not live together.

Much of the correspondence tells us of intimate practicalities, recriminations, misunderstandings, complications. What is striking is what the letters do not contain. The war is scarcely mentioned. Events of the past (in the case of the excerpted letter we bring, the event is a review of Celan’s work which Celan felt was anti-Semitic) are darkly alluded to (“Vorkommnisse aus der schlimmen Zeit im vergangenen Jahr “). Perhaps one doesn’t elaborate on the difficult things one has lived through. There is little talk of art, literature, philosophy. Non-literary concerns are the topic of the day. Please don’t fly, Celan warns in one letter. I heard about your new book from someone else. Why didn’t you send me your latest book of poems yourself, she admonishes him. Crises large and small. Imagined or justified. Yet they seem almost always to be Celan’s crises. One cannot come away from this book without feeling he was a tad on the side of egotism. His problems are the focus. He is a man plagued by demons. They drive him though his days, culminating in his abortive attempts to kill his wife, her subsequent successful abandonment of him, and his final plunge into the Seine in 1970.

Bachmann’s dies three years later in Rome. From wounds suffered from an apartment fire, after she falls asleep in bed with a cigarette burning…

Ingeborg Bachmann is the consummate poet of post-war melancholia. Listen to her reading of her own poems on an excellent site dedicated to her memory (www.ingeborg-bachmann-forum.de). She is one of the few writers whose work you really can fall in love with, because it is so sad, so felt, so lyrical (yes she had the gift of song). She in fact wrote very little poetry during her life. But one feels she is a poet, not a proser, though she did “turn to prose”, produced a novel, some short stories, radio plays and opera libretti to the music of Hans Werner Henze. Her poems are elegiac in tone and they remind me sometimes of Brecht, sometimes of Trakl. (Which is not to say that she is like them.) Hers is the tradition emerging out of Goethe, Hölderlin and Hofmannsthal, deep within the deepest stream of German poetry. And yet her poems are as sad as an Irish ballad.

In mentioning her new boyfriend, Paul Celan, to her parents, Ingeborg Bachmann says he is a surrealist. I am not sure surrealism is the mot juste. Surrealism, if one is to be precise, goes back to Tristan Tzara and the boys and was inspired by automatic writing. Celan’s poems are too worked to be surrealistic. But they are perhaps non-rational, non-linear. And there is often something of the chant about them. Sometimes the poem is a set of disparate pictures, plucked down and allowed to rest within the body of the poem. Other times the poem becomes a kind of compulsive mantra that approaches the hypnotic. Hypnotism isn’t far from surrealism of course. I read his famous poem Todesfugue as a Zwangsidee, a recurring thought the poet can’t get out of his head. Listen to Celan reading it and you will notice that he makes the poem accelerate, transforming it to an inwardly moving spiral that can only end, slowing down, as a single point (http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=4yS3zuucngc). His poems proceed from melancholic depths, as do the poems of Ingeborg Bachmann. But the colors of the two poets differ. Celan’s poems are sometimes like broken flowers, sometimes like shattered glass. Bachmann’s poems are a dark flow, glittering in the night.

I believe Celan's first poem of his first book was called “Ein Lied in der Wüste”. It begins: “Ein Kranz ward gewunden aus schwärzlichem Laub…

Bachmann’s first poem in her first book seems to be “Ausfahrt”. It begins: “Vom Lande steigt Rausch auf.”

In the land of poetry, after the second world war, they were the ones. The true poets.

Looming in the background of these letters, is the “Nachkriegszeit”, the late forties and the fifties. It is a time of immense fear, fear of the Russians, THE BOMB and it is pervaded by an atmosphere of spiritual emptiness. This is the time of Billie Holiday, the saddest Miles Davis, Paul Celan and Ingeborg Bachmann.

Read Herzzeit if only to dip into the world of Paul Celan and Ingeborg Bachmann, though the letters Madame Celan wrote to Ingeborg Bachmann are deeply moving. She, the one who had to be tolerant of what was going on between her husband and Ingeborg Bachmann. She is the one who would have to leave Celan because he was too crazy. And she is the one who had the greatness of soul to forgive and understand.

Herzzeit

Ingeborg Bachmann -- Paul Celan

Der Briefwechsel

Mit den Briefwechseln zwischen Paul Celan

und Max Frisch

sowie zwischen Ingeborg Bachmann

und Giséle Celqn)Lestrange

Herausgegeben und kommentiert von

Bertrand Badiou, Hans Höller,

Andrea Stoll und Barbara Wiedman

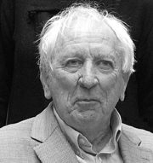

Speaking of letters, a new book has appeared in Danish, which includes the correspondence, in the years between 1964 and 1990, of bosom buddies the American poet Robert Bly, and the Swedish poet Tomas Tranströmer.

Over the years, both have translated poetry into their respective languages, each other’s poetry and the poetry of others. And this is what is so interesting about the book. AIRMAIL is its title, and it has a predecessor in Sweden that is not as ample as her younger Danish sister. There are more letters in the Danish edition.

AIRMAIL bears witness to the efforts of two poets who did their best to get their translations right. They stumble sometimes through the preliminary stages of translation, and we chuckle with them as they make errors or stand dismayed before a phrase they cannot comprehend. We see Bly translating the Swedish word for glasses (glasögon) as glassy eyes, or Tranströmer wondering what “crystal in the sideboards” can possibly mean. But they work and work until they get it right. Indeed they take the work of translating and helping the cause of poetry very very seriously, trying to arrange tours for one another or others, putting out poetry magazines that would give their readers some insight into the other country’s poetry and furthering generally the cause of the word.

We read these letters with a combination of admiration and gratitude for the works these fine poets have done.

AIRMAIL

Breve 1964-1990

Tomas Tranströmer

Robert Bly

på dansk ved Peter Nielsen and Karsten Sand Iversen

Forlaget Arena and Forfatterskolen

In Danish